Culture of the Yaeyama Islands

The Yaeyama Islands, at the southern edge of Okinawa, are known for their natural beauty, but their deeper richness lies in culture. Here, festivals, textiles, music, language, and spirituality form a living tradition passed down through generations. To understand Yaeyama is to witness the rhythm of village rituals, the craftsmanship of weavers, the sound of the sanshin lute, and the quiet reverence of sacred groves.

Festivals and Rituals

Festivals are central to Yaeyama life. They are not staged events but living traditions that bind communities together, linking people with ancestors and the natural world.

Harvest Festival (Hōnensai)

Held in every village around July or August, following the lunar calendar, the Harvest Festival is one of the most important annual events. On the first day, known as On-puuru, villagers gather at the utaki, a sacred location, where the first crops, awamori liquor, and dances such as lion performances are offered to the gods. On the second day, Mura-puuru, the entire village takes part in celebrations with folk dances, tug-of-war, and colorful processions. Visitors are welcome to observe, though some sacred parts of the ritual remain closed to outsiders.

Harvest Festival (Hōnensai) in Yaeyama: villagers celebrate with tug-of-war, and prayers for a good harvest.

Dragon Boat Festival (Haarii)

In May, at fishing ports across the islands, wooden dragon boats decorated with vivid colors race across the water. This ritual, called Haarii, is held to honor the sea gods and pray for safety and abundant catches. The sight of dozens of rowers paddling in unison, urged on by drummers and chants, is both exciting and deeply symbolic of the islanders’ reliance on the ocean.

Haarii Dragon Boat Festival: teams paddle decorated boats to pray for safe seas and abundant catches.

Angama (Obon Ritual)

During the Obon season in the 7th lunar month, ancestral spirits are welcomed back to the community. In Yaeyama, this takes the form of Angama, in which troupes led by two masked elders—Ushūmai (old man) and Nmi (old woman)—visit homes accompanied by drummers and dancers. The elders engage in humorous question-and-answer exchanges with the living about the afterlife, blending reverence with laughter. In Ishigaki City, public Angama performances allow visitors to witness this unique tradition.

Yaeyama Angama masked elders Ushūmai and Nmi with performers during Obon

Jūrokunichi-sai (16th Day Festival)

On the 16th day of the first lunar month, families gather at ancestral tombs for what is sometimes called the “otherworld’s New Year.” Food and awamori are offered to the spirits, and families eat together at the tomb site. Schools close early to allow children to participate. Though it is a private ritual, knowledge of it reveals how deeply ancestor worship is part of everyday life.

Traditional Crafts

Crafts in Yaeyama are not simply decorative; they are carriers of meaning and history.

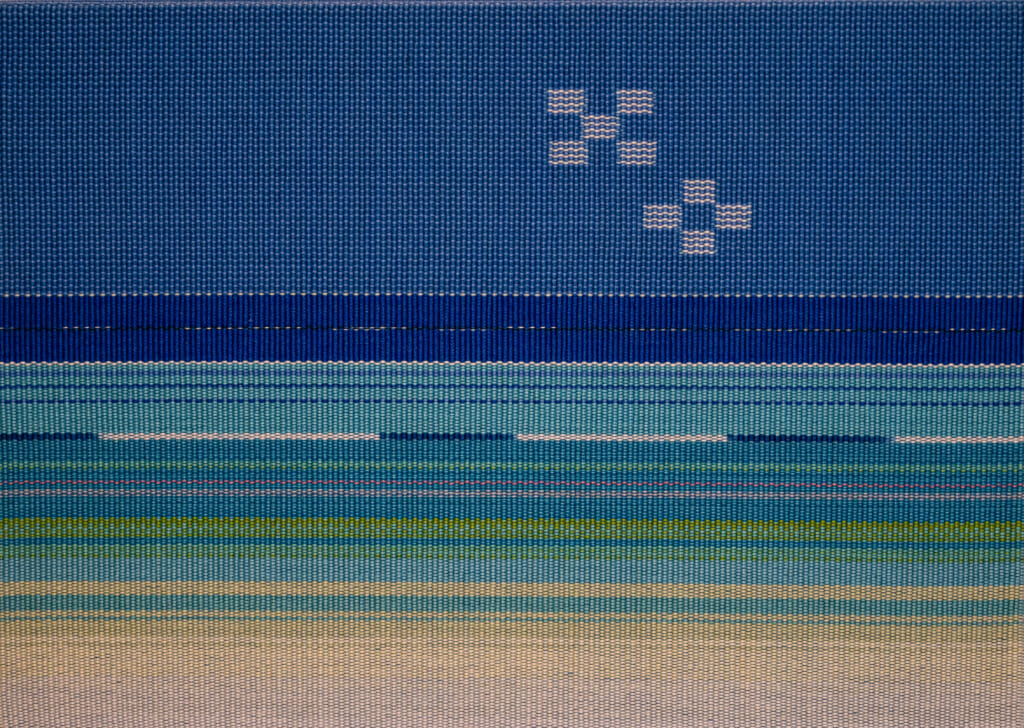

Yaeyama Minsa-ori

Yaeyama Minsa weaving: the five-and-four square pattern means “forever” — a symbol of love.The best-known textile of the islands is Minsa-ori, a sturdy cotton weave with the distinctive “five and four” pattern. This motif symbolises itsu yo, meaning “forever and always.” Historically, young women wove Minsa belts and gave them to men as tokens of enduring love. The centipede-leg side patterns carried another message: “visit often.”

Today, Minsa weaving continues in Taketomi and Ishigaki. Workshops use local plant dyes to create rich blues and browns, and artisans weave on wooden looms. Visitors can try weaving a small piece themselves. A scarf or wallet woven in the Minsa style is more than a souvenir—it is a continuation of a 400-year-old tradition.

Other Island Crafts

Beyond Minsa, the islands are home to other crafts:

Yaeyama Jōfu, a fine linen made from ramie, once a tribute textile for the Ryukyu Kingdom.

Natural dyeing, using plants such as indigo and Fukugi, producing vivid yet earthy tones.

Pottery and basketry, including rustic shisa lion-dog figurines and palm-leaf hats.

Each craft reflects the island environment and the values of resilience and beauty in daily life.

Music and Dance

Music and dance are woven into the rhythm of life in Yaeyama. They are not only for entertainment but for work, worship, and community celebration.

The Sanshin and Folk Songs

The three-stringed sanshin, with its traditional snakeskin-covered body, is the instrument most associated with Okinawan music. In Yaeyama, it accompanies almost every song and dance. Yet the oldest musical forms were sung without instruments: It were call-and-response work songs performed while planting or walking. Over time, the sanshin and drums were added, giving rise to the folk ballads (shima-uta) that are still performed today.

Sanshin musician on Kabira terrace

Famous songs such as Asadoya Yunta and Tubarama originated here, capturing the lives and emotions of the islanders. Every August, Ishigaki hosts the Tubarama Contest, where singers perform this traditional ballad in the local style.

Eisa Drum Dance

The dynamic drum dance known as Eisa originated on Okinawa’s main island but thrives in Yaeyama as well. During Obon, youth troupes march at night, spinning and pounding large drums in unison. The power of Eisa is unforgettable: the chants, the rhythm of the drums, and the sight of young dancers illuminated by lanterns create an atmosphere both festive and sacred.

Yaeyama Folk Dance

Yaeyama dance is distinct from the courtly dances of Okinawa. Performed in simple attire such as cotton kimono or banana-fibre cloth, these dances are more restrained and spiritual. Many are linked to agricultural rituals to pray for fertility of the land. Watching one of these performances is to see tradition in its most solemn and enduring form.

Language: Yaimamuni

The Yaeyama dialect, known as Yaimamuni, is part of the Ryukyuan language family and is distinct from Japanese. Each island has its own variation, and UNESCO lists the dialect as endangered. Though younger generations speak standard Japanese, the dialect is still heard in folk songs, rituals, and among elders.

Even a single phrase, spoken with respect, often leads to smiles and friendly exchanges. The survival of Yaimamuni in song and ritual demonstrates its importance to identity, even as everyday use declines.

Discover Yaimamuni

So, why not learn a few local words? It will unlock a bit of Yaeyama’s soul. Here are some Yaeyama words that you might find useful or interesting:

おーりとーり (Oori toori) – “Welcome!” A greeting used in Yaeyama. You might see this on welcome signs or hear it at hotels.

にぃふぁいゆー (Niifaiyuu) – “Thank you.” This is “ありがとう” in Yaeyama dialect. Some locals pronounce it ミーファイユー (Miifaiyuu) as well. Express your gratitude in the island way – e.g., “Niifaiyuu” for the delicious meal.

Spiritual Practices

Religion in Yaeyama blends animism, ancestor worship, and Buddhist influences. Sacredness is often tied to the land itself.

Utaki (Sacred Groves)

Utaki in Ishigaki island

In place of grand shrines, Yaeyama villages have utaki, natural sites such as groves, rocks, or caves believed to house deities. Each village has at least one, and ceremonies are still performed there. Misaki Utaki in Ishigaki, for example, is dedicated to a sea deity and remains one of the most revered sites. Visitors should admire such places quietly from outside, as entry is often restricted to community members.

Priestesses (Tsukasa / Noro)

Historically, spiritual life was guided by women known as tsukasa (or noro in Okinawa). They were responsible for seasonal rites, agricultural prayers, and household rituals for the fire god (Hinukan). This tradition of female spiritual authority is a defining feature of Ryukyuan religion, and in Yaeyama traces of it survive in both community ceremonies and family practices.

Ancestor Worship

Ancestor veneration is central to life in Yaeyama. It is expressed in public festivals such as Obon and private ones such as Jūrokunichi-sai, but also in daily offerings at household altars. In Yaeyama belief, the boundary between the living and the dead is thin, and maintaining a relationship with ancestors ensures balance and well-being.

Experiencing Yaeyama’s Living Culture

For visitors, engaging with culture in Yaeyama requires respect and openness. You may watch a tug-of-war at a harvest festival, listen to sanshin music in a tavern, or try weaving a piece of Minsa cloth. Or you may hear the dialect in a folk song.

These are not performances for tourists but parts of daily life. By approaching them with understanding, you gain more than memories: you touch the spirit of the islands.

The Yaeyama Islands are often praised for their beaches, but it is the culture—expressed in rituals, crafts, music, language, and spirituality—that gives them their depth. To experience it is to step into a continuity of tradition that has endured for centuries and still thrives today.